The Just Energy Transition Partnership for Indonesia announced last year – with more details due in mid-2023 – targets coal-fired power plants. Nithin Coca reports on how it will, and will not, change the country’s energy system.

Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous country and fifth-largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter, is crucial to the success of the Paris Agreement and any attempt to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C. However, as a developing country still highly dependent on natural resources and fossil fuels, it has long been clear that it will not decarbonise without significant international support. That is why many are hopeful about Indonesia’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), announced in November 2022 alongside the G20 Summit in Bali, Indonesia, as COP27 was playing out in Egypt. It promises $20bn in financial support, is led by the US and Japan, and includes other developed countries like Canada, the UK, France and Germany.

“The international partners should help… Indonesia to define a coal phase-out or phase-down strategy,” says Achmed Shahram Edianto, a Jakarta-based energy analyst with the climate think tank Ember. “For the US and Japan, as leaders of the Indonesia JETP, we expect more technological knowledge transfer, capacity building and assistance with financial mechanisms that can lower the risk of developing renewable energy.”

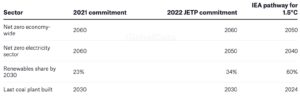

Indonesia’s JETP was the second globally following one announced for South Africa in 2021. It was followed by a third for nearby neighbour Vietnam just weeks later in late 2022. While the details of Indonesia’s JETP are set for release sometime in mid-2023, according to the initial joint statement, the goals are to peak “total power sector emissions by 2030”, bring the sector’s net-zero target forward by ten years to 2050 and “accelerate the deployment of renewable energy… to at least 34% of all power generation by 2030″.

Indonesia’s JETP falls short of a 1.5°C-aligned pathway

Indonesia’s national commitments versus IEA pathways

Indonesia’s JETP: Focus on coal

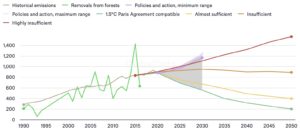

Historically, Indonesia’s emissions have primarily come from land use change and forestry, notably deforestation due to the expansion of the palm oil, paper pulp and mining industries. Land use change and deforestation have, since 1990, made up more than 50% – and in years with widespread forest fires, up to 80% – of Indonesia’s GHG emissions.

That is changing, however. Alongside some progress on slowing down deforestation, Indonesia has seen its consumption of fossil fuels rise. According to the US-based non-profit Global Energy Monitor, coal accounted for 195 million tonnes (mt) of Indonesia’s CO2 emissions in 2022 – the seventh-highest for any country’s coal fleet in the world, just below the figure for Germany – while total energy sector emissions grew to 650mt in 2019. This has been driven by a massive expansion of coal-fired power generation capacity over the past 15 years.

Climate Action Tracker, another non-profit, ranks Indonesia’s climate commitments as “highly insufficient” on a 1.5°C pathway and says the “international community has a critical role in helping Indonesia to implement a coal phase out”. That is where the JETP could be decisive, says Achmed.

Indonesia’s targets depend heavily on the forestry sector

Indonesia’s emissions in different domestic pathways and scenarios for global warming, MtCO2e/year, 1990–2050

Source: Climate Action Tracker

The JETP is actually just one of five different Energy Transition Mechanisms (ETMs) that are being implemented in Indonesia. Another is being led by the Asia Development Bank and the three others are domestic. This includes one led by the national electricity company PLN, one led by the government’s Indonesia Investment Authority and another led by the state-owned infrastructure company PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur, or Persero.

All three domestic schemes will also target coal retirement, with 23.2GW of capacity identified so far. PLN’s ETM also has the goal of increasing Indonesia’s renewable energy capacity to 16GW by 2030 – but how all these schemes will work together remains to be seen. They are all looking to attract both public and private finance.

“There is a lot of money coming into Indonesia, or already allocated from the state budget, for the energy transition,” says Martin Baker, director of strategy and communications at the Jakarta-based non-profit Traction Energy Asia.

Beyond coal-fired power plants

Since its first nationally determined commitment (NDC), or national climate plan, was submitted to the UN in the run-up to COP21 in 2015, Indonesia, like other developing countries, has always provided two figures for its emissions reductions targets – one without international support and one with international support. In its latest NDC, submitted in September 2022, the unconditional target was a 32% reduction below a business-as-usual baseline by 2030, going up to 43% with international support.

While the focus is on getting this support from other governments, the private sector is also expected to play a key role. According to US-based non-profit RMI, half of the JETP’s budget, or $10bn, will be mobilised from private financial institutions that are part of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). There are many questions about how those funds will be used and whether they will come in the form of loans or grants. GFANZ declined an interview request from Energy Monitor, as did the Indonesia Coal Mining Association.

Fitch Rating Singapore, a credit ratings company, said in an analysis that the JETP and other ETMs could push Indonesian coal producers “to consider investments to diversify away from thermal coal, which could have an impact on ratings”. Elrika Hamdi, an energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a think tank, says the industry should be ready for this.

“Coal players… have experienced… how difficult it is to get funding for new coal-fired power plants, or mines,” she told Energy Monitor. “Institutional investors and lenders already have in place strict divestment policies for coal.”

Hamdi sees some positive signs that Indonesian coal companies are indeed diversifying. “The top ten coal companies [in Indonesia] have started to invest in greener technologies like solar, wind, hydro, geothermal and electric vehicle-supporting facilities like batteries and charging stations,” she says. One example is Adaro Energy, the second-largest coal miner by production volume, which launched a “Green Initiative” to invest in biomass, hydrogen and solar power in 2021.

Loopholes: from coal plants… to coal plants

Some are concerned that Indonesia’s JETP, like South Africa’s, focuses only on grid-connected coal-fired power plants, ignoring not only other GHG sources but even the use of coal outside of electricity production.

Indonesia is a major coal exporter, ranking number one or two in most years for thermal coal exports, primarily for use in coal-fired power plants in other parts of Asia. Part of the reason for the buildup of domestic coal-fired power production capacity in the past decade has been to increase domestic coal consumption as export markets became less reliable, also due to climate policy.

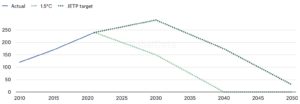

Indonesia’s power sector needs to reach net zero by 2040 to be 1.5°C compatible

Power sector emissions in JETP (IEA APS) scenario and 1.5°C (IEA NZE) scenario, MtCO2

Source: Ember, adopted from IEA report ‘An Energy Sector Roadmap to Net Zero Emissions in Indonesia’

However, with major financiers Korea, Japan and China announcing an end to funding all overseas coal plants, the coal industry has also been looking for alternative ways to use coal. One is coal gasification, which can provide an alternative to natural gas or petroleum in industrial, chemical or transport applications. As reported by Energy Monitor in 2021, the Indonesian government’s coal gasification plans could, if fully realised, consume nearly as much coal as the country’s entire coal-fired power fleet – and negate its commitment to phase out the use of coal in power generation by 2040.

Another potential loophole is the use of coal in what are called ‘captive’ plants. These coal-fired power plants are not connected to the grid but are used to power factories or industrial parks. Global Energy Monitor estimates there is 5GW of operating captive coal power in Indonesia, with another 4GW under construction. Some of these plants are being built to power aluminium smelters and processing facilities for minerals like cobalt and nickel, for use in the global electric vehicle and battery supply chains.

Will Indonesia’s JETP help make space for renewables?

Many see scaling up renewables as key to displacing coal, and the inclusion of the 34% renewables target in the JETP joint statement is seen as potentially giving a boost to the country’s lagging solar and wind power sectors.

“Currently, there is no real renewable energy sector in Indonesia, because it doesn’t make economic sense,” says Martin, pointing to a lack of incentives such as a feed-in tariff. “The state power utility, PLN, still makes it very difficult for solar to go on to the grid,” he says.

The Indonesian Parliament is debating a New and Renewable Energy bill that, in theory, should address some of the issues facing renewable energy in Indonesia, but Baker is concerned by how “new” is being defined. “It [the draft bill] strongly incentivises coal gasification, carbon capture and store, and biomass, but it does not incentivise solar, wind or geothermal enough,” he says.

Indonesia currently gets a paltry 0.2% of its electricity from solar, and only 0.5% from wind, despite abundant available solar and wind resources across the archipelago. Geothermal energy – for which Indonesia has more estimated potential resources than any other country in the world – also remains vastly underdeveloped, says Baker.

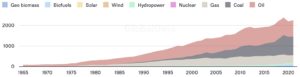

Solar and wind made up only 0.07% of Indonesia’s electricity consumption in 2021

Electricity consumption by source, TWh, 1965–2021

Source: Our World in Data

For Hamdi, there is merit to focusing on phasing out coal first, particularly on the Java-Bali grid, home to more than half the population. “Currently, for Indonesia, because of overcapacity, a coal phase-out and retirement needs to be done as early as possible, as it will create room for renewables to enter,” she says.

The next few months will be crucial. Baker, Achmed, Hamdi and others are hopeful that Indonesia will, as promised in the joint statement, engage with civil society as it develops both the details of the JETP and its implementing policies.

The impact will be felt globally, not only because of Indonesia’s size and GHG emissions but because it will provide lessons for other developing countries dependent on fossil fuels that are seeking assistance with their energy transition.

“Indonesia will not be the last country who will receive this kind of international support,” says Achmed. “It is important for Indonesia to show its commitment and be a leader for [other] developing countries.”

This article already published in energymonitor.ai entitled:”How will Indonesia’s JETP move the country beyond coal?”